Project-based learning has been shown to help youth develop important STEM skills, content knowledge, and 21st century competencies.1 Giving students a chance to drive their own investigations in the classroom sounds great, but it can be difficult to oversee a dozen or more projects in one class. One of the first hurdles faced with independent inquiry-based projects is helping students narrow down their ideas to doable research questions.

The 2006 book Students and Research by Cothron, Giese, and Rezba2 suggests an activity called the Four Question Strategy. The students begin with a broad topic, such as “plants”, and answer four questions that list out the resources available to them, a set of independent variables to try, and a set of dependent variables to observe. In this blog post, we’ll walk through this brainstorming activity and provide a slide deck for you to use with your students.

The four questions students will answer are:

- What materials are readily available for conducting experiments on (topic)?

- How do/does (topic) act?

- How can I change the set of (topic) materials to affect the action?

- How can I measure or describe the response of (topic) to the change?

Question 1 asks students to come up with a list of materials that are readily available to them. When doing this activity with students, it helps to add some scaffolding questions such as, “what do we have in the classroom right now?” and “what could we buy at a local store with just a little money?” Do not move on to question 2 until all ideas have been recorded. Below is an example of how students might answer the first question with the topic of “plants.”

Question 2 prompts the students to think about how the topic in question behaves. It can be helpful to reword this question if it doesn’t quite make sense with the topic. Take ice for instance: “how does ice act?” might sound odd while “what does ice do?” could make more sense to your students. Below is a sampling of answers to this question, continuing with the topic of “plants.”

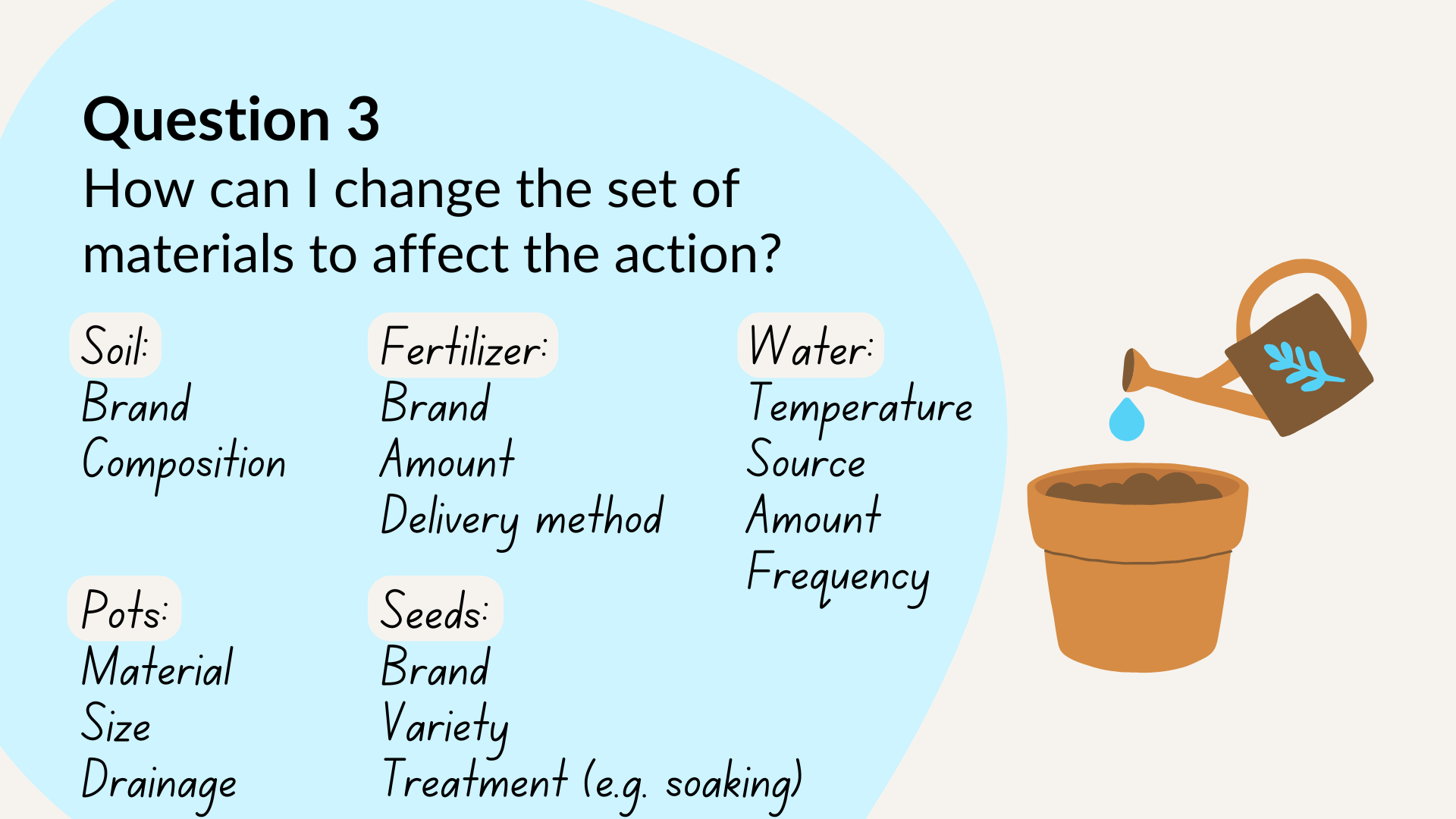

Question 3 builds off of question 1 to develop some independent variables. It is helpful to remind students that you’re looking for ideas of what they could change, to see if it makes a difference. The temptation here is for students to jump right into designing an experiment. Steer them back to simply answering the question at hand. Consider going through each item from question 1 and doing a mini brainstorm about that before moving to the next item. Below is an example of answers to question 3 with our topic of “plants.”

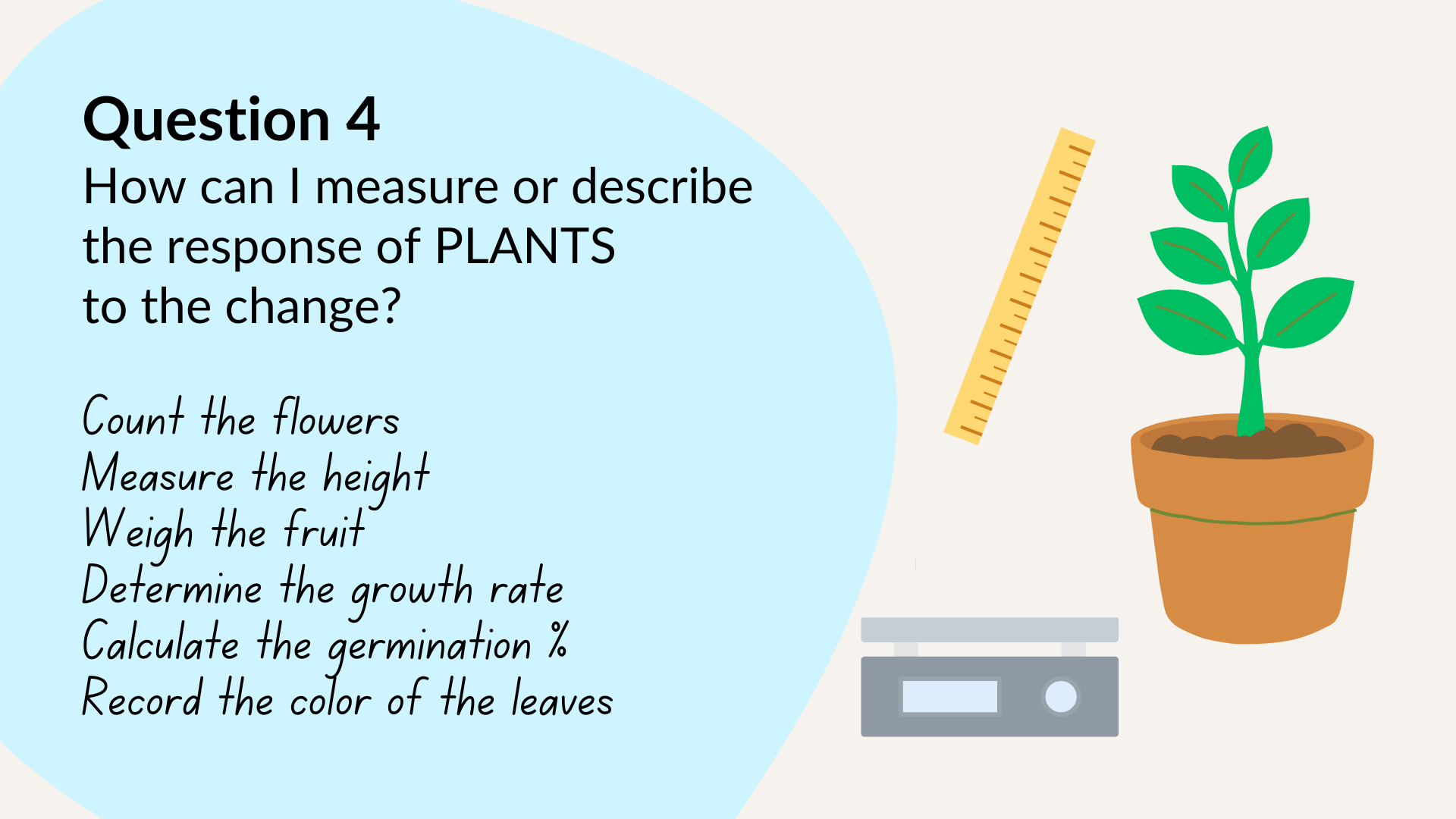

Question 4 uses the dependent variables from question 2 to inform data collection and experimental design. Students should keep in mind the resources available to them (from question 1). Often students think of measurement tools they missed when answering question 1. They may also think of new things they could observe about their topic that they could add to question 2. Encourage them to add these new ideas to the lists they created previously. Again, there is a impulse to think ahead to designing an experiment, but encourage them to simply answer question 4 as completely as they can. Below is a sampling of answers with our topic of “plants.”

Once your students have a complete set of lists from the Four Question Strategy, they can begin piecing together research questions and hypotheses in this way:

Step 1: They will select an Independent Variable from question 3 and a Dependent Variable from question 4. They will identify their Constants, which is everything else from question 3. These Constants are the things they attempt to keep the same throughout their experiment and across all of their test groups.

Step 2: Next, they fill in the blanks to build their Research Question using those variables from step 1: Does the [Independent Variable from Q3] affect the [Dependent Variable from Q4]? They may want to reword their Research Question if it sounds awkward.

Step 3: Finally, they will form their hypothesis by predicting how a change in their Independent Variable will affect the Dependent Variable. For example, they may choose a specific brand of soil that they believe will result in a better germination percentage than any of the other soils tested.

After walking through this brainstorming activity, it is easy to see how one topic, such as plants, can spur so many unique investigations. It does not need to stop there, however. This full-class activity can be a precursor to small-group brainstorming sessions on different topics. A few topics that work well with for the Four Question Strategy include water, baseball, ice, and cookies. Once students feel comfortable using this structure, they can go a step further to ask the four questions using any topic that interests them. To support you, we’re providing a Four Question Strategy slide template to adapt for your own use on Canva.

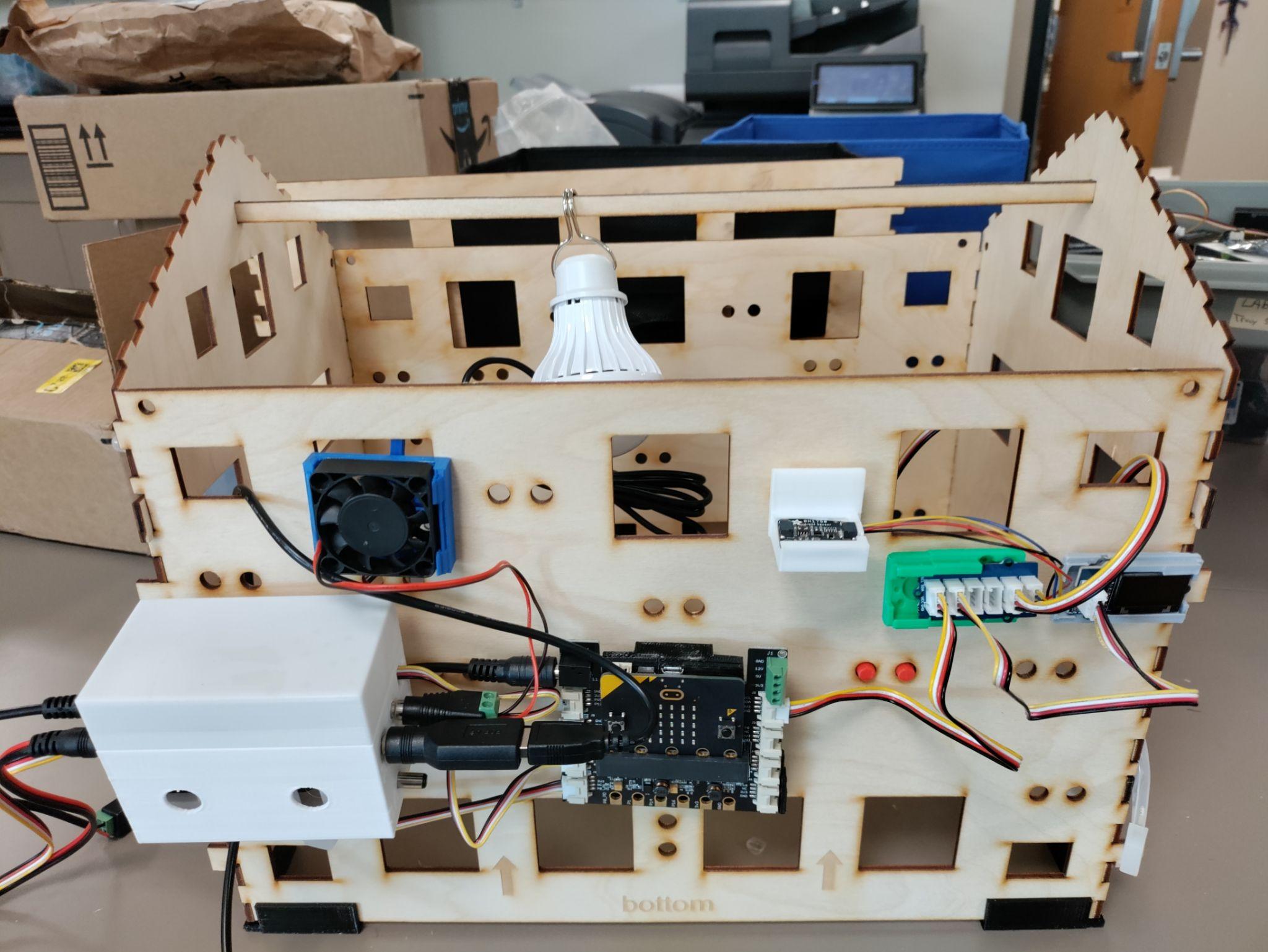

MMSA has two projects with close connections to the Four Question Strategy: our Science & Engineering Fairs for middle school and high school, and a new collaboration with Boston College that uses Smart Greenhouses to facilitate Transdisciplinary STEM Learning. Contact Stefany Burrell, sburrell@mmsa.org, for more information about either of these opportunities.

References

- Power, R. 2019. Technology and the curriculum. Power Learning Solutions. Accessed 11 October 2024: https://pressbooks.pub/techandcurr2019/chapter/pbl-competencies/

- Cothron, J. H., Giese, R. N., & Rezba, R. J. (2006). Students and research: Practical strategies for science classrooms and competitions. Kendall/Hunt.